Common Eider

There are six subspecies of Common Eider recognised:

- Pacific S. m. v-nigrum — of north east Siberia to north west North America; wintering Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands.

- Northern S. m. borealis — of the Arctic Atlantic; wintering around north Atlantic coasts as far as the Gulf of St Lawrence.

- Hudson Bay S. m. sedentaria — of Hudson Bay and the James Bay region.

- Dresser’s S. m. dresseri — of north east North America; wintering from Gulf of St Lawrence, south to Long Island, New York.

- Faeroes S. m. faeroeensis — of the Faeroe Islands, British Northern Isles and Outer Hebrides.

- European S. m. mollissima — of northern Europe; wintering on the French coast and the Mediterranean basin.

Somateria mollissima

For many years, Common Eiders were seldom kept in starter wildfowl collections due to their special dietary requirements. With a little consideration for their need for protein they are undemanding, now that we have specialist feeds available. They are confiding, very ornamental and their acceptance of people makes them a firm favourite with many.

Eiders are almost entirely carnivorous. Their strong bills and excellent diving ability allow them to utilise their principle diet, the mussel, throughout the year. The bills of kept birds may need gentle filing if there is no natural abrasion whilst foraging.

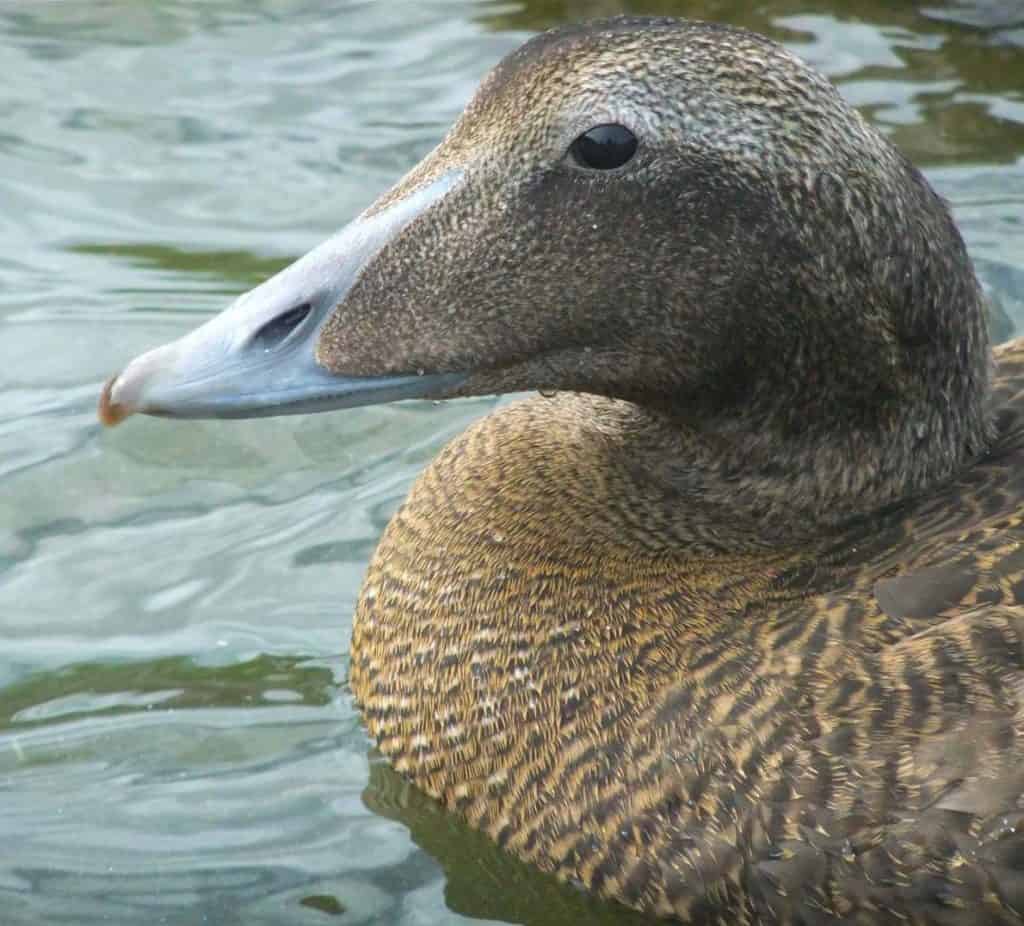

Common Eiders have a distinctive black crown, pale green nape and black and white body plumage. The drake has a dove-like cooing call whereas the duck has a repetitive and hoarse call rather like grunting. There is something conspiratorial about the sound of eiders; it is almost as if they know of some scandal or other that should not be spoken about!

Like many sea ducks, eiders mostly keep close to the shore. During breeding time their preferred habitat is sheltered shallow coves and bays or islets. They will nest on remote islands and spits along low-lying rocky coasts and estuaries, sometimes a little further inland. Once sitting, the duck can be very reluctant to leave the nest, relying on her exceptional camouflage.

The insulating properties of eider down has long been prized and wild colonies have been managed in Iceland for centuries. Protection from predators, managed nesting sites and assisted rearing allow a limited harvest of down from each nest.

The presence of European Eiders on the Northumbrian coast was appreciated by Saint Cuthbert, a monk, bishop and hermit of the early Northumbrian church. During his contemplative retirement, he was surrounded by them.

In Northumberland, it is still known as the Cuddy Duck after him. While on the Farne Islands, he instituted special laws to protect the ducks and other seabirds nesting on the islands. Eiders still breed in their thousands off the Northumberland coast, however some east coast populations have declined in recent years. These declines are common to the European Eider population, and while the other subspecies’ populations appear stable, this species was uplisted to globally Near Threatened in 2015. Consequently, this species is also Amber-listed in Britain; the European subspecies is Red-listed and the Faeroes subspecies, which is an internationally-important declining breeder here, is Amber-listed.

In the wild, the Common Eider is a colonial nester. They nest on the ground, filling their nest with a large amount of feather down. Eiders tend to lay 4–6 eggs which they incubate for 26–27 days. Ducklings often congregate in small crèches once they have left the nest, led to a safe area by a responsible female.

Download a colouring page here.

FURTHER READING

Brandslet, S. (2019). Norwegian SciTech News. Eiderdown farming — a living cultural tradition.

Hollmen, T. (2021). Marine Bird Sensitivity to Hydrocarbons. Alaska Sea life Center.