Birds that are not in full health will often hide their symptoms well. It may be that an ailment is pretty serious before the symptoms show. Our suggestions below are given in good faith. The intent is to provide a general overview but is not a replacement for specialist veterinary care. Click here to see some vets in the UK who have avian knowledge.

Angel Wing

Angel wing happens when the growth of the wing feathers outstrips the muscle ability to hold the wing in the natural position. It is nearly always due to an imbalance in feeding: too many calories and a deficiency of essential elements. Left untreated, the bird will be unable to fly properly. It might be reasonable to assume that there will be discomfort too.

Flight (and other) feathers in birds are surrounded by a waxy sheath when they emerge. This is filled with blood as the feathers lengthen. These ‘pin’ feathers are heavy and if growth is too rapid, the muscle and tendon development of young birds does not keep up. Wing slipping is where the wing is too heavy to hold up, and the bird drops it to the floor. This can be worthy of taping and treatment, but it is distinct from angel wing because the wing remains in alignment. Angel wing is specifically the twisting of the metacarpals away from the radius.

If caught early and treated straight away, both problems can be corrected. Treatment is best done by one person holding the bird and another doing the taping.

The growing outer portion of the wing should be gently held folded in the natural position. Use a strip of micropore tape to hold it there, following the natural curvature of the wing. Leave a small tab of extra tape-to-tape in the armpit region to allow for growth.

Take care not to damage the quills where they emerge from the skin. Remove the tape after 2 days and re-tape for another 2, reassess and repeat if necessary. There may be a little damage to individual feathers, but after the next moult this will be gone.

Prevention is better than cure. Make sure your feeds are properly stored and in date, so the vitamins and minerals are present (they degrade with time and also if damp). Move growing stock onto a grower ration as soon as feathers start to appear. Starter crumb is only intended for the start of life. By a week old, start weaning by mixing grower pellet in with the crumb. Aim to be 100% grower pellet a few days later.

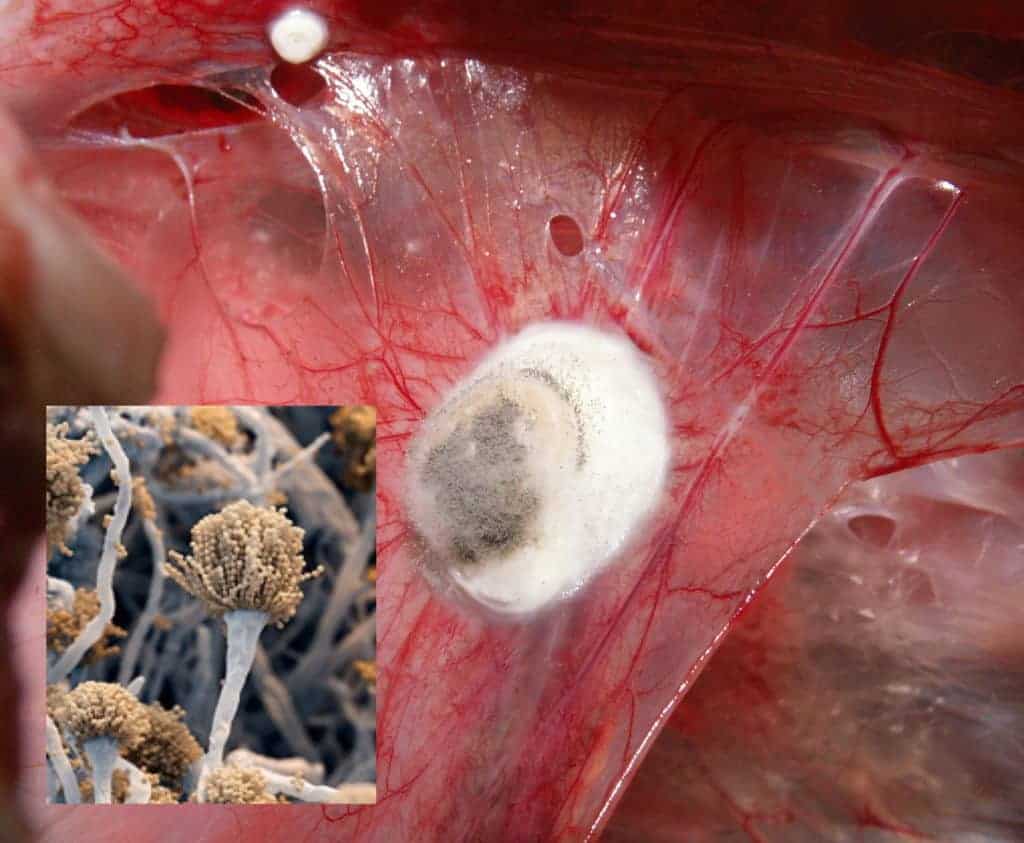

Aspergillosis

Spores are all around but multiply particularly well in damp rotting vegetation. If enough fungal spores are inhaled by birds, they multiply and produce lethal legions in the lungs and airsacs. Eider and Arctic breeding wildfowl are particularly susceptible.

Waterfowl can be more prone when stressed. For instance; when they have worms, following a predator attack, in hot weather or even after being moved.

The Aspergillus spores grow well too on damp bark chips so it is wise to avoid these as a ground substrate in your pens. We suggest pebbles, shells or sand as an alternative, especially for Arctic species which have no natural immunity. These include the eiders and scoters.

Laboured breathing, poor appetite and general weakness, occasionally accompanied by sticky eyes are an indication of aspergillosis. Never use hay as bedding for nest boxes or housing. Mouldy food and poor storage of pelleted foods are another possible source of fungal infection. Aspergillosis is a very challenging disease to cure. Treatment is by prescription only and expensive, may be prolonged and not effective in severe cases. It will involve oral dosing daily for some time, the stress of doing this further debilitates the bird.

Beaks or Bills

The end of a bill is a hard nail of keratin known as the bean. Underneath is a fine network of nerves. Sometimes the bean can become overshot, often because the bird has no need to forage and wear it down naturally.

The bean can be trimmed carefully with nail clippers. This should be done progressively and in good time. Any doubts, take the bird to the vet.

Broken Bones

Young birds are more prone to injury than older ones. You should bear this in mind when catching up and moving birds. Prevention is always better than cure, so take a look round your pens and think about any places a bird can become trapped.

Breakages can heal well, and remarkably quickly. Longer bones will need to be set and splinted by the vet. You need to protect and immobilise an injury for the journey. A product aimed at the emergency medical market and worth keeping in your first aid kit is SamSplint. This can be cut with shears to fit the bird. Use Micropore tape to hold it in place. It is always a balance between causing further injury and killing the bird through stress.

In all cases, isolating the patient after treatment can help. It needs to be protected from being picked on by other birds. Make a small enclosure with easily accessible water and shelter from the sun and wind. Swimming is often the best form of therapy and a dry, clean loafing area is also important.

Curly Feet and Toes

Toes can be deformed by an accident, poor development in the egg for a number of reasons or by inherited defects. Some problems can be corrected if caught and treated early.

Occasionally after hatching, a foot might not flatten out. The bird walks on its toe knuckles. This can happen if the hatching is slow or too much moisture has been lost from the egg. A small ‘boot’ can be made from a plastic food container and taped in place for a couple of days. Once the foot is used in the natural position for a few days, development is almost normal.

Congenital deformities can happen because of inbreeding. It is wise not to add these birds to the breeding flock. Consideration should alays be given to the comfort and welfare of the bird.

Bumble Foot/Corns

Bumble foot is a bacterial infection entering the foot through a crack or cut causing a swelling on the underside of the foot. This can happen in dry, hot conditions when the bird is running on hard ground, or from an injury caused by sharp objects in the enclosure, so do check your enclosure regularly. Bathing with salt water may help. However if it persists and a hard core/abscess develops under the skin, this has to be removed and veterinary advice should be sought. Corns can be prevented by adding rubber car mats to harsh concrete pond surrounds.

Feather Lice: Trinoton spp., Anaticola spp

Signs: Presence in the lacrimal ducts produces epiphora (excessive tear production), large numbers indicate severe systemic disease.

Diagnosis: Direct visualisation in the skin and feathers.

Treatment: ivermectin, fipronil but not in domestic waterfowl. Beware ivermectin toxicity in some ornamental geese.

Leeches: Thermyzon spp

Signs: Head shaking, sneezing, conjunctivitis.

Diagnosis: Direct visualisation in nasal passages, sinuses and peri-orbital region.

Treatment: ivermectin, manual removal, water treatment. Pans of salt water may allow sea ducks to flush their nostrils themselves.

DVE - Duck Viral Enteritis

Also known as duck plague, the cause is an anatid herpes virus 1. It is shed in faeces and can be transmitted by ingestion or inhalation. Susceptibility depends on species but a wide range of infected waterfowl species has been described. It is believed to be introduced via wild waterfowl such as Mallard which may have roosted on sewage farms.

The clinical signs are peracute death, bleeding from the gut seen orally and from the vent, ocular discharge and avoidance of light, convulsions – do not confuse the terminal convulsions of drowning with DVE. Birds are found dead overnight. The most risky time for DVE to appear is when the soil warms up in March, but it can appear during the warmer months.

Diagnosis is by viral isolation and identification from affected tissues e.g. oesophagus, liver, spleen and intestine. Serological tests are available. A post-mortem examination will often show bleeding from the gut, and the diagnosis can be made with histopathology.

Unfortunately there is no treatment for affected birds. Inactivated and live attenuated vaccines can be used in birds over two weeks old, it requires 2 initial doses, followed by annual boosters. To protect for the most vulnerable time of year, adults should be vaccinated in February. Removal and incineration of carcases is important after an outbreak plus decontamination of water and enclosures where practical.

Introducing something new should be a gradual process.

Egg Binding

Birds laying for the first time, or the sudden return of cold conditions can be the stressors causing females difficulty in passing eggs. Symptoms of egg binding are the bird looking hunched up with feathers fluffed out and generally looking miserable. Sometimes with gentle handling you can feel the egg in the lower end of the oviduct.

See also Prolapse, below.

Birds may be helped by being put in a darkened brooder box with a heat lamp (red bulb), raising the temperature up to 85ºF but allowing room for the bird to move away from the heat if it wishes. Warmed olive oil applied to the cloaca may be of some help.

It is vital not to break the egg inside the cloaca because the lining of the oviduct is very delicate. Damage from a broken shell can lead to peritonitis (blood poisoning). If the egg does break you should seek veterinary advice immediately.

External Parasites

Every species has its own form of feather lice. They may be difficult to see, often they are the same colour as the feathers. Lice cause irritation and prevent birds from resting and eating properly. Several species of leeches affect waterfowl and take a blood meal. They can lodge anywhere on the bird but are probably most troublesome in the nasal passages.

Feather Lice: Trinoton spp., Anaticola spp

Signs: Presence in the lacrimal ducts produces epiphora (excessive tear production), large numbers indicate severe systemic disease.

Diagnosis: Direct visualisation in the skin and feathers.

Treatment: ivermectin, fipronil but not in domestic waterfowl. Beware ivermectin toxicity in some ornamental geese.

Leeches: Thermyzon spp

Signs: Head shaking, sneezing, conjunctivitis.

Diagnosis: Direct visualisation in nasal passages, sinuses and peri-orbital region.

Treatment: ivermectin, manual removal, water treatment. Pans of salt water may allow sea ducks to flush their nostrils themselves.

Frostbite

Ice and snow present challenges to birds, particularly as many waterfowl are outside all year. Frostbite is a real danger to webbed feet, especially where there is no natural cover or ponds are shallow. Most commonly kept species can cope with the cold provided they always have open water. Deciding which species are right for your collection will depend on what facilities you can provide and where you live.

The circulatory system of birds minimises heat lost through the unfeathered feet by a heat exchange system. The arteries supplying warm blood to the legs pass very close to the veins returning to the heart, so some of the outgoing heat warms the blood coming back. When arterial blood reaches the foot, it is very cool, so less heat is lost in transfer with cold water. Blood flow is carefully regulated to maintain the delicate balance of providing blood and nutrients but maintaining core temperature.

The small amount of heat reaching the feet may not be enough to stop the tissue from freezing in extreme weather. Where the blood flow stops, areas of tissue die and can be lost. This is seen as blackened tissue which can drop off, but possibly not before some infection sets in. We should assume that there will be pain asscociated with this condition. At the very least, the bird is disfigured. It may ultimately lose the use of the limb.

During periods of prolonged snow, a life-saver can be an open shelter. An ideal shelter is closed on the top and two or three sides to protect the birds from wind and snow. A thick layer of substrate such a sand or straw will allow birds to get away from cold, wet or frozen soil, reducing the chance of frostbite. Heated pads or soil warming cables can be useful. Heat lamps can be added to the shelter to keep the birds warm and dry, but do be aware of electrical safety. If in any doubt, consult an electrician.

Good stockmanship relies on observation. The shelter must be of adequate size for the species and number of birds in the enclosure, and the birds should feel comfortable in them. You should watch closely for any signs that shy birds are being excluded by the bully-boys. Wildfowl in particular do not enjoy confinement. However, if you are calm and quiet around them, they will adapt for short periods. Stressed birds are far more prone to disease so you must be doubly vigilant.

Heat Stress

On the whole, birds from temperate regions are better at keeping warm than keeping cool. It is important to provide shade.

Birds do not sweat, but can regulate their body temperature to some extent by panting.

In very hot spells some may enjoy a spray of water, having cool water available helps them cope. A fine mist from a garden hose may be welcome, as will a dish of ice cubes.

Some keepers choose to house their birds under cover when summer temperatures are excessive.

Not all species have the sense to stay out of the sun when it is hot. Do not assume that birds will make the connection with shade and cooler temperatures in the way we do. Introducing something new should be a gradual process.

Limps

A limp is always worth investigating and early treatment is usually the most successful.

Birds that are limp are usually in pain, and a vet should be consulted to treat the cause of the limp and alleviate the pain of the bird.

Inspect the bird in the hand for thorns, cuts, bumble foot, dislocation and breakages. Small wounds of the feet and legs happen from time to time. Bush prunings, particularly if thorny, should always be removed from waterfowl pens.

Internal parasites can cause lameness so this should be considered if a bird is limping.

After treatment for minor injuries, a short period of confinement in a small enclosure away from boisterous fellows will allow natural healing to happen.

Worms and Parasitic Diseases

There are several different types of worm that are known to affect waterfowl. In the wild many species of tapeworm and flukes appear to live in harmony with their hosts. Numbers can build up and become a problem where waterfowl are gathered closely together and at greatest risk of sharing parasitic diseases. Routine faecal testing (and on new birds brought into the collection) should be done to assess the health status of the birds and treat them properly.

Young stock can have a slight immunity, inherited from their parents. The immune system takes time to become robust, so we recommend that young stock are turned out onto fresh pasture. Short grass allows sunlight to get to the soil, killing off some of the egg cysts.

Signs of significant worm burden include:

- Limping or being unable to walk at all

- Losing weight

- Apparent ‘coughing’ or beak gaping

- Head shaking as if to dislodge something

- Drop in egg production

- Worms seen in the droppings

- Blood in faeces or around the vent

Several worm species can build to dangerous levels. Thus, a routine programme of cleaning and resting pens and ponds should be devised. Treatment with anthelmintic drugs can be done routinely, say twice a year, at the start and end of winter. Alternatively, where stocking density is low and pasture rotated, worming can be carried out when an excessive burden is suspected. Several veterinary labs offer analyses for parasites. These results could allow you to target your treatment more specifically.

A course of wormer should be repeated after 3 weeks in severe infestations. This will deal with eggs picked up after treatment and before they reach maturity.

Parasitic worms:

- a) Tracheal:Syngamus spp, Cyathostoma bronchialis.

b)Proventricular: Echinuria uncinata

- c) Capillaria:Capillaria contorta

- d) Caecal: Heterakis sp.

- e) Conjunctival: Oxyspirura mansoni

Diagnosis: coughing, lethargy

Treatment: Flubendazole, preferably outside the breeding season.

Air sac mites:Cytodites nudus

Signs: Cough, dyspnoea.

Diagnosis: Observation in air sacs and airways.

Treatment: ivermectin.

Haemoparasites: Plasmodium sp. Leucocytozoon sp. The latter can be problematic during the summer when more vectors are present, young birds are more seriously affected.

Signs: Lethargy, weakness, anaemia.

Diagnosis: Observation of parasites in a blood smear.

Treatment: Chloroquine.

Coccidiosis: Eimeria sp, Tyzzeria sp, Cryptosporidium sp, Wenyonella sp.

Signs: Weight loss, anaemia, renal disease, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, tracheitis.

Diagnosis: Tracheal/conjuctival swabs, faecal exam.

Treatment: Amprolium, toltrazuril, sulfa-trimethoprim, paramomycin.

Toxoplasmosis: Toxoplasma gondii reported in geese.

Signs: Anorexia, anaemia, emaciation, CNS signs, diarrhoea.

Diagnosis: Serology.

Treatment: Clindamycin.

Trichomoniasis: Trichomonas sp.

Signs: White-ish plaques in mouth and oesophagus, regurgitation, weight loss.

Diagnosis: Wet mount smears from areas affected.

Treatment: Carnidazole.

Schistosomiasis: Dendritobilhargia pulverulenta, these trematodes invade intravascular spaces in some part of their life cycle, very common in diving ducks and geese.

Signs: Multisystemic signs. Reported as cause of encephalitis in swans.

Diagnosis: Histological exam of affected tissues, flukes in aorta.

Treatment: Praziquantel.

Hardware Disease

This is a term used in North American collections and is very descriptive. Foreign objects picked up by curious birds cause damage to the oesophagus and the gut lining and can lead to peritonitis (blood poisoning). It is especially important to collect up all screws, bits of metal and wire, netting staples etc. that may be dropped when carrying out maintenance.

Lead Poisoning

Waterfowl are particularly vulnerable because they routinely pick up small stones and grit; shot, fishing weights and pellets look much the same and end up being ground up in the gizzard.

Open Wounds

Even a small amount of blood can look very alarming. Skin can be broken during mating, fighting or contact with sharp objects. When treating a wound it is important to know if there is any underlying tissue damage. No two wounds are the same.

Open wounds look horiffic, but birds have a wonderful ability to heal. The wound should be cleaned and an assessment made as to how it can be protected as it heals. Dressing an avian wound is possible with a number of products available from your chemist. In general, if the wound exposes bone or muscle, it will need a suture. This procedure is best done by a vet.

It is wise to isolate the patient so that other pen mates are not drawn to peck at the wound. Make a small enclosure with easily acessible water, shelter from the sun and wind and most importantly, protection from harrassment by other birds. A dry, clean loafing area is also vital. Keeping the injury clean helps and you should consider veterinary help with pain relief.

When feathers are growing there is a sheath of keratin around them which is filled with blood. Sometimes this can be damaged and there will be bleeding. As long as the bird is not unduly stressed or being harassed, this will heal quickly. Catching the bird may do more harm than good, you can try observing it through binoculars to have a closer look at what is going on.

Generally it is best not to catch birds up and move them whilst the wings are ‘in pin’ or ‘wet’ unless they are calm and used to being handled.

Orphaned Birds

Wild waterfowl imprint on one or more parent, most ususally the mother. This bond keeps the family in a tight group after the hatchlings leave the nest. If the mother is killed, the youngsters (often called downies) will tend to stay together but will be vulnerable to predators and extremes of weather.

Poultrykeeper.com has advice on raising wild ducklings.

When we raise downies artificially, they do best in social groups. A single youngster is not always easy to raise and would generally be better off with others of similar size, even if they are a different species. If this is not possible, a small cuddly toy or even a sock ball can be placed in the brooder.

Many species of waterfowl learn social cues from their family group, especially when it comes to mating behaviour. Large wintering flocks of different species can be seen intermingling in the wild, but they generally mate only within their own kind. In captivity this separation becomes fuzzy and anything goes.

Paying attention to which species are likely to hybridise is an important part of planning a mixed collection.

Postmortem

Sadly if you have livestock, eventually there will be deadstock. Waterfowl are relatively long-lived and generally enjoy good health. If you do have a loss, it is important to know why.

Any veterinary practice will be able to advise you about getting an autopsy performed. Although there will be a cost involved, it could be money well spent, especially if it highlights an issue where your management can improve.

Post-mortem investigation is particularly useful to confirm a diagnosis of disease, or perhaps prove that the initial diagnosis was incorrect.

Looking into the anatomy of a bird is an interesting exercise and it will improve your knowledge and understanding of how birds function. If you perform a basic autopsy yourself, always wear surgical gloves and a face mask. Dispose of these and your tools properly and wash your hands thoroughly in soapy water. There are some diseases in birds that are zoonotic, that is they can be caught by humans.

Prolapse

Waterfowl are unusual in the bird world in that they have a phallus (intromittant organ). Occasionally it does not retract, and so is at risk of injury. Risk factors with this condition are over-activity, mating on land instead of water or simply age. Some female waterfowl can also prolapse the oviduct.

See also Egg Binding, above.

If the phallus does not retract, it is easily damaged. Other birds may nip at it and on land it can pick up grit and abrasive vegetable matter.

Some species of stifftail have an unusually long phallus which takes some time to retract. Sometimes the member can get snagged. If you are certain that the bird needs assistance, you can try bathing the member in lukewarm water and gradually reduce the temperature. Cold water helps to reverse the process. If required you can use a lubricant, such as KY jelly to pop it back in. If this fails, you may have to take him to the vet to have the phallus removed.

Where the oviduct prolapses, it is important to question why this has happened. Particularly in domestic birds, young ones may strain with their first clutch. As with the male phallus, the tissue can be gently replaced, but this may need to be done by the vet.

It is vital not to break an egg inside the bird. The lining of the oviduct is very delicate. Damage from a broken shell can lead to peritonitis (blood poisoning).

Slipped Tendon

The tendon running through the trochlear groove of the hock can sometimes slip inwards (medially). This means the foot can no longer be extended. Though some waterfowl are adept at hopping, the strain of doing so places greater risk of injury on the other limb.

Stress

Individuals are affected differently by stress. A hormone known as Cortisol is produced naturally by the body to balance many parts of the metabolism. When subjected to stress, the level of production increases. Cortisol also supresses elements of the immune system, especially the cells that orchestrate a lot of the body’s protection from infection, so barring autoimmune diseases, it’s a given that it plays a part.

What might cause stress in a bird?

- Overpopulation

- Dirty water

- Poor diet

- Thirst

- Fighting

- Injury

- Pain

- Excess of drakes

- Separation from a mate

- Parasite burden

- Cold

- Heat

- Fear

- Disturbance from pets

- Predator attacks

- Frequent catching

- Moving home

Central to the five domains of animal welfare is mental state, surrounded by nutrition, environment, health and behaviour. A problem with any of these areas could lead to stress. Our responsibility is to provide a safe and fulfilling environment, where our charges may live a healthy and happy life.

We should review our practices regularly to ask ourselves what is best for the birds.

Most areas of the metabolism are inter-related. For instance, a parasite infestation would cause stress and predispose the bird to other conditions. A stressed bird might be more prone to becoming overburdoned with parasites, so it is a vicious circle. Breaking the cycle comes down to good husbandry.

Ticks

Many birds pick up ticks and if healthy, they will not suffer unduly. Due consideration has to be given though to the possibility of disease transfer. Catching birds to remove ticks may cause more stress than leaving them to drop off naturally. You will have to make a decision which option to take based on the level of infestation vs the nature of the bird.

The mouthparts of ticks are easily separated from their body and this must be avoided. The jaws will stay in place and allow an entry to the blood system, possibly leading to infection. It is also important not to squeeze the swollen body of the tick, potentially pushing infected fluid back into the bird’s system. Tick removers are readily available at pet stores and it is worth having them in your first aid kit. They have a fine v-notch, which with a deft twist will remove the offending insect completely.

Topical treatments for parasites are effective against ticks.

In some areas, ticks are responsible for spreading Lyme disease. Lyme disease is a serious bacterial infection, and can affect humans. Keeping the grass short will help to reduce the incidence of ticks.

Vision

Any significant trauma to an eye needs to be seen by a vet, thus giving the bird the best possible chance to retain its sight. Small bits of fluff and seed husks occasionally lodge in the eyelids, but on the whole, waterfowl keep their eyes clean by regular immersion. This is one of the reasons why clean water is so vital for their wellbeing.

Waterfowl have 3 eyelids; one each top and bottom, and a third or ‘nictitating membrane’, which moves under these two from front to back.

Occasionally an eye may be lost due to physical damage or infection. It may be necessary to have an infected eye removed by a vet. Waterfowl can get cataracts, often in one eye. One-sided vision does not impair a bird in captivity unduly. However, it should be monitored for bullying by other birds, who may take advantage of the impairment.

Although a totally blind bird may get along adequately in an area it is familiar with, serious consideration should be given to the bird’s quality of life. Every effort should be made to monitor any deterioration in its ability to function. Euthanising is never done lightly, but, it is sometimes the kindest outcome.

Wet Feather and Broken Feathers

The preen (uropygial) gland is particularly well developed in waterfowl and we are all familiar with the nibbling and wiping that waterfowl do as part of their hygiene ritual. The oil from this gland does not actually waterproof the feathers but it does keep them supple and slightly water repellant. The physical barrier of the contour feathers locked together forms an ‘overcoat’, which cover the down feathers that trap air both for temperature regulation and buoyancy. Waterfowl know their survival is dependent on keeping the overcoat, or ‘integument’, in good order, so a high proportion of their time is spent on preening.

Wet feather refers to the loss of integrity of the feathers. There are two elements to such problems: loss of production of oil from the preen gland and physical damage to the barbs and barbules which allow the feathers to ‘zip’ up. Think of a line between these 2 points and a problem with feathers will fall at some point between them.

The preen gland can become infected or less productive with age, and this will certainly affect the ability of the bird to keep the feathers in a good condition. Factors that cause physical damage to the feather include hard pond edges, oily debris on the water surface, mud, overpreening, and, occasionally, feather mites.

With the contour feathers damaged, the down is exposed, and the bird tends to fiddle with the patch. It may paddle furiously when on the water, attempting to keep the patch dry.

The instinct to preen is so strong that feathers can be damaged when birds over preen. Some birds may do that when they are under stress. The barbules break and the bird knows something is not right, so preens some more and makes it worse. If it is simply mechanical damage (without underlying feather mite, preen gland problem, etc), the problem may go away when the bird next moults. However, it may happen again and may get worse in older birds.

The stress of having wet feather may also lead to other problems, such as aspergillosis.

Another cause is the Cladosporum spp of mould that lives on willow trees in particular. This can grow on the feathers and thus cause over-preening. Washing the bird may help but would also cause stress. Not having willow trees in an enclosure is the obvious long-term solution here and after removal of the willows, once the bird(s) moult, the feathers should grow back again normally.

If the primary cause of the wet feather is a preen gland infection or feather mites, these should be treated. Similarly, any management problem must be addressed, including reducing stress factors for birds that over preen. Affected birds will likely know their own limitations and may avoid the water. Those normally keen to stay in the open may seek shelter from the rain. It may be necessary to keep them under cover during the coldest and wettest months. You should ensure that their diet is sufficient, as they will use more energy to keep warm than a healthy bird.

As with all matters of health, stress and poor conditions increase the likelihood of problems.