In an ideal world, female waterfowl should incubate their own eggs. However, for a number of reasons this is not always practical in captivity. We may remove eggs because the mother is not a good sitter or is being disturbed by other birds. Sometimes if the first clutch of eggs is taken away, it is possible that the female will lay a repeat clutch in the same season.

Going ‘broody’ is a natural phenomenon with nearly all birds that incubate eggs. It is particularly obvious in female waterfowl. Males may guard nests; some species may even share the incubation. It varies from species to species how much involvement drakes, ganders and cobs have in the raising of the family. This may influence our decision whether or not to parent rear. Geese and swans, where males play a parental role, are frequently more successful.

One method for larger ducks and geese is to take the eggs, as they are laid, and replace them with dummies of near identical size and weight, until the clutch is complete. Then, should a predator find the nest, at least some of the eggs may be saved. However, despite this risk, it may be better to leave small duck eggs in the nest rather than exchanging them for dummies. Very small bantam eggs, matched for size and weight, may be an alternative substitute but not always. Some of the smaller teal can be very suspicious of any disturbance and are better left until the clutch is complete.

Egg Collecting, Storage and Record Keeping

Memory, especially with several different species or broody hens sitting, can be embarrassingly unreliable! It is therefore recommended that a simple record (on a card) is kept with each clutch. Notes can be taken on a smartphone too, but hard copy is still a sensible option. The species; the date incubation started; and the anticipated date of hatching should be written down. Notes on the nature and effectiveness of the broody or location of the nest might be kept too.

Cleanliness is one of the best ways to improve your success with incubating. Take a fresh container with clean straw and soft lining. You should also have a separate bag to carry any obvious addled eggs, the aim is to prevent transfer of harmful bacteria. Eggs should be stored on a tray of sand in a cool place. A wine cabinet is one option for storing eggs. The ideal temperature is around 15°C. A few degrees above or below this figure while the clutch is being collected should do no harm to the eggs. Normally a clutch takes up to 14/16 days to complete.

The eggs should be turned a couple of times a day, as the mother would do each time she returns to the nest. As soon as down from the mother bird’s breast appears, covering the eggs in the nest, it can be assumed that the clutch is close to being completed. Clear the nest of dummies and scrap the nest site if you want to encourage the bird to lay again.

Artificial Incubation

The type of incubator you choose will depend on how many eggs you plan to set and what your budget is. They all work on similar principles: to replicate the temperature consistently that the parent bird would provide, allow fresh air around the eggs to let carbon dioxide escape and have some means of turning the eggs. Automatic humidity control is available on most machines. The accuracy and sophistication of incubators largely depends on what you pay.

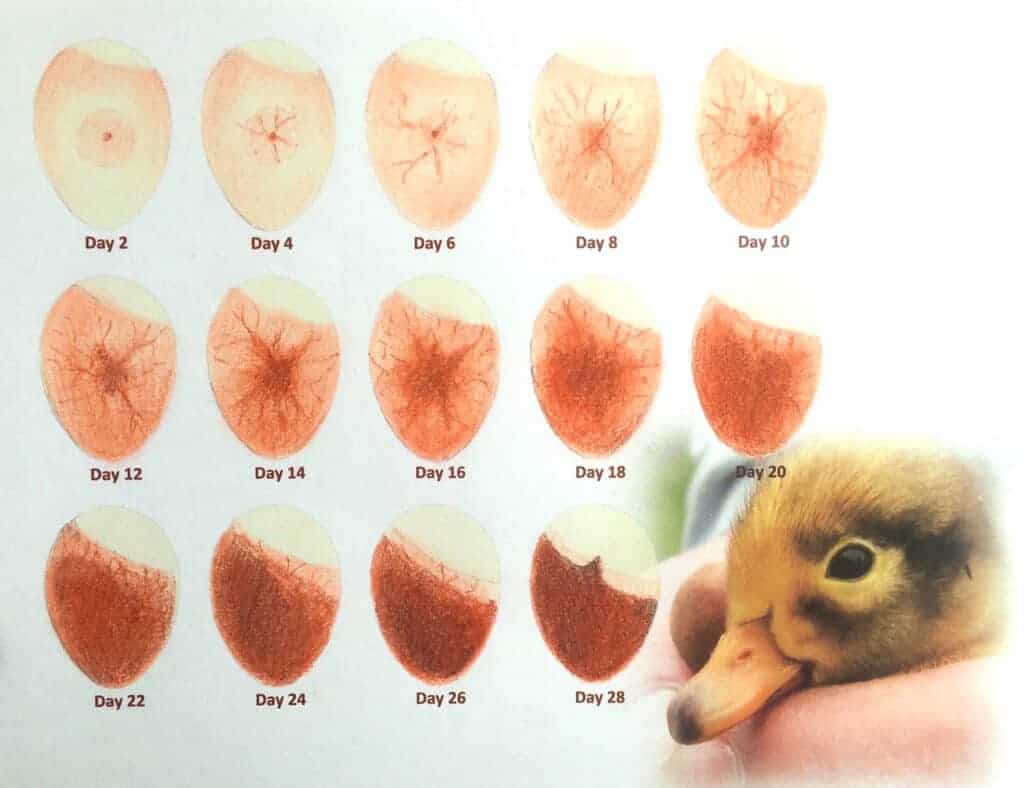

Hygiene is really important. Eggs should be checked regularly by candling (a strong light shone through the egg). Any eggs not developing should be discarded before they contaminate healthy eggs. When the correct incubation period is close to completion, be ready to move the eggs to a hatcher. It really is best NOT to allow eggs to hatch in the incubator but done in a separate hatcher.

Broody Hens

Using a broody hen is a very traditional but effective way of incubating.

The ideal broody is steady, quiet, clean of feather on feet and does not mind being handled. Good broodies are hard to come by so it is best to keep your own flock. You need a ‘bank’ of spares, ones that have proven themselves and in turn should have been bred from, to fix the characteristics you require – the incubation and rearing of the waterfowl. Silkies, Sumatra Game, Scots Dumpies and crosses of these breeds are cited by many as being the best sitters.

For a modest collection, a bank of three to six broody boxes and a series of short netting covered runs are needed. When the hen has gone broody, she should be gently moved from the run to the box. This is a good time to treat her with a proprietary delousing agent. A base layer of clean sand, covered with leaf mould or a sod of grass, shaped into the form of a nest, should fill the bottom of the box. A few dummy eggs should be left under the broody for a day or two to test her. All this is best done in the evening. The next evening, she needs to be lifted from the broody box for exercise in her run, and then the dummy eggs can be removed, and the waterfowl eggs slipped in.

An experienced breeder will candle the eggs once or twice during incubation – it is best after 10 days and again after 20 days. As you would do with eggs in an incubator, eggs are candled by shining a bright light through the egg. Any which are completely clear after 10 days are infertile and if, after 20 days, you cannot see clear signs of blood vessels then the embryo has most probably died and is going rotten. Such eggs should be removed so they don’t contaminate the good ones.

Broody Care

The broody boxes need ventilation holes and should be kept in the shade or under shelter to avoid heat stress to the broody in hot weather. She needs to be allowed off the eggs at least once a day, fifteen to twenty minutes on average, at the same time each day. She should have water and food receptacles that she cannot turn over in the run. Wheat, cut maize and a little grit is suitable food. She must have time to both feed and pass a dropping during this period. If possible, a dust bath should be provided. Experience with the individual hen will tell you whether you have to shut her out with the slide from the eggs or not. Some will hurry back to the eggs before defecating with unpleasant results later for the eggs, hen and handler!

Although the broody will be turning the eggs herself, she may need help to turn larger goose eggs, and the breeder should do this as a routine precaution. During dry conditions it may be beneficial to dampen the ground around the broody boxes.

Hatching

You will need to check incubation times for the breed or species you have. ‘Downies’, as young waterfowl are often termed, will be heard calling within the eggs up to forty-eight hours before they are due to hatch or the eggshell has been chipped. The broody will sit tighter and will be less inclined to leave the nest for food or exercise. It may take seventy-two hours for all, or the majority of the eggs, to hatch.

Light spraying of the chipping eggs with tepid water might be beneficial at this stage, especially in periods of dry weather.

The downies will not need food for twenty-four hours or so, since they have yolk reserves to draw upon for sustenance.

Rearing

At this stage a brooder should have been prepared which will house both hen and downies on clean ground. Preferably it should be an area of closely mown grass upon which waterfowl have not been kept recently, to avoid potential parasite problems.

This is where a good broody really proves her worth, not only as an incubator, but brooder too. Depending on the species, chick crumbs, turkey crumbs and duckweed should be introduced for the young. This will be sampled by the broody and she will coax the downies to try, and indeed to eat. Water should be available in shallow trays filled with smooth pebbles so that the young don’t get too wet before their down and preen glands have become active. The brooder, hen and downies should be moved onto fresh clean ground every day.

Finally, all broody boxes and incubating equipment should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected ready for the next valuable batch of eggs or young to be hatched this season, or the next.