Geese depicted in an ancient Egyptian tomb were not of any species living today, detailed analysis confirms. Instead, there are good reasons to think they were a faithful representation of an extinct species, giving us an insight into how these birds looked we would never obtain any other way.

When you're looking for accurate depictions of species no longer with us, ancient Egyptian art might not be your first thought. Besides all the gods with bodies of humans and heads of other animals, Egyptian artists' misrepresentation of human movement has been commemorated in song.

However, Dr Anthony Romilio of the University of Queensland told IFLScience that this highly stylized art is a product of the New Kingdom from 3,600 years ago. Old Kingdom painting is actually remarkably realistic, particularly one stunning work found in a tomb beside Egypt's Meidum Pyramid and sometimes referred to as 'Egypt's Mona Lisa'.

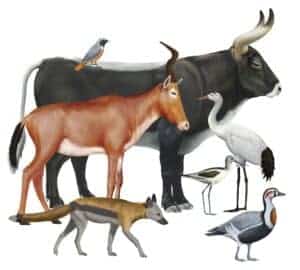

The painting includes depictions of three species of geese. None of these now dwell in Egypt, something that has led some to question the painting's authenticity. However, 4,600 years ago when the painting was made, the Sahara was in the process of changing from grassland to desert, supporting species now long gone.

Another aspect of the painting that has puzzled many, according to Romilio, is why two of the species of geese are superbly accurate, while the other has many differences from the nearest counterpart Red-breasted Geese Branta ruficollis. The explanation that the artist simply got it wrong fits poorly with the work's superbly accurate depictions of other geese species and leopards and jackals on the exterior walls.

An alternative theory is that the artist had seen a subpopulation of Red-breasted Geese that looked a little different from those we know today. Romilio explores this in the Journal of Archaeological Science, but comes to the conclusion the birds in the painting are simply too different from modern B. ruficollis to be the same species. Instead, the artist was using now-extinct creatures as models.

Romilio used the Tobias criteria, a way of identifying distinct species of birds, to reach this conclusion, the first time this has been done from an artwork, not a specimen. Ideally, for such distinctions, we would know things the painting does not reveal, such as the geese's honk, but Romilio made do with what he had.

'The major differences are the patterning of the face,' Romilio told IFLScience, 'With very different markings and colouration, and the strikingly different neck colours. The wings and back are also light grey instead of black.'

So has Romilio discovered an extinct species entirely unknown to science? Possibly, but a skull has previously been found in Crete of an extinct goose species clearly closely related to, but different from B. ruficollis. We know nothing else about it, but it's quite possible its migratory range took it to Egypt.

Romilio notes cave art has been used to reveal the existence of several extinct species, some of which have been matched to fossils. If nothing else, this has prevented the mistakes we sometimes make when envisaging animals from their bones.

Other extinct species are also portrayed in Old Kingdom art, but usually ones known about from other sources.

Romilio has made something of a career from extracting information about extinct creatures from unexpected places. He once obtained photographs and measurements of dinosaur footprints, now inaccessible to scientists, when a casual conversation alerted him to materials stored for decades in a cupboard under a house's stairs.