Birds use their large, prominent eyes to search for food and detect predators. They can see objects in fine detail two-and-a-half to three times farther away than people can, and their spectral sensitivity, which spans from near-ultraviolet (UV) to red, is far beyond that of humans. With eyes set on the sides of their head, most waterfowl view the world mostly with monocular vision (each eye is used separately) rather than binocular vision (both eyes view the same object at once). The head tilting allows them to use the sharpest part of their vision when it really matters — such as being vigilant for predators.

Although each eye can see from the top of the bill c180°or more, to behind the nape. The overlap of the two eyes' images is a fairly narrow strip over the centre of the head. They don’t rely on it in the way we do. The two halves of the bird brain are only partly interconnected.

Suspended between the left and right hemispheres of the human brain sits the corpus callosum, a thick bundle of nerves. It acts as an information bridge, allowing the left and right sides to rapidly communicate and act as a coherent whole. Although the hemispheres of a bird's brain are not completely separated, they don’t process the information from both halves together as we do. It seems to pay to concentrate on one thing at a time.

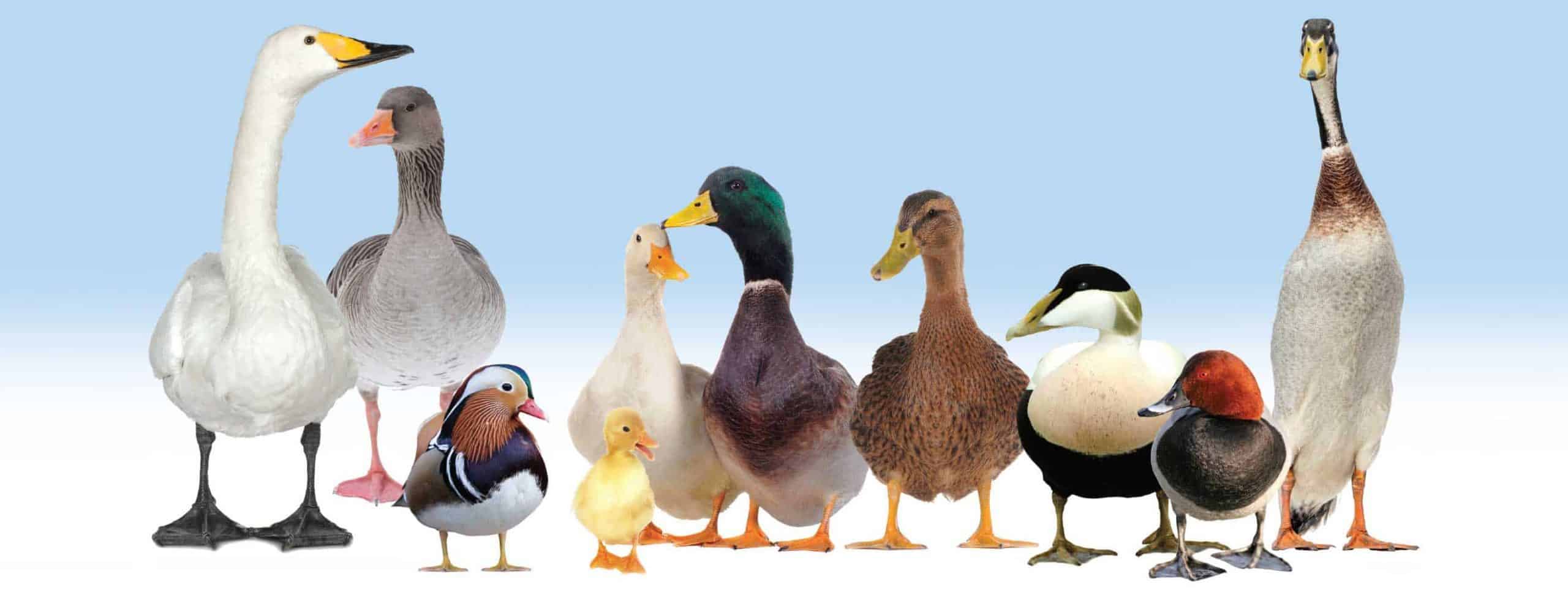

What did scientists notice when they put all their ducks in a row? See for yourself: